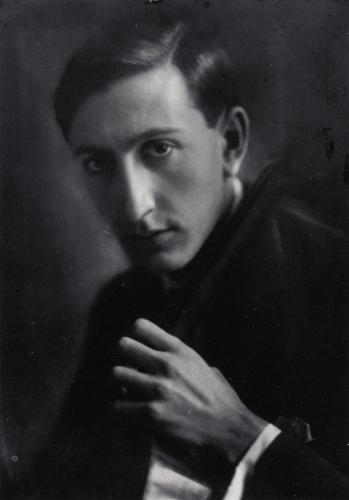

Paul Hermann

Cellist and composer Paul Hermann steered into a new direction, several times during his life, to escape from the claws of anti-Semitism. As a young musician, there was no future for him in Hungary and he set off to Berlin. But in 1933, life in the dynamic metropolis became increasingly difficult. He performed as long as he could throughout Europe, with his own music and works by his teachers Kodály and Bartók. Ultimately, in Toulouse, Hitler's long arm caught him.

by Carine Alders

With a cello through Europe

Paul (Pál) Hermann was born on March 27, 1902, in a well-to-do neighborhood in Buda. The amusing story goes that young Paul only would practice the piano if he received a penny for each etude he played. It is unknown who gave him his first cello lessons, but at the age of thirteen he attended the Franz Liszt Academy. He became friends with violinist Zoltán Székely, pianist Géza Frid, and their teachers Zoltán Kodály and Béla Bartók. He studied cello with Adolf Schiffer and composition and chamber music with Leo Weiner.

On a spring afternoon in 1918, Hermann was on the same tram back home as Zoltán Kodály, a teacher who was just ten years his senior. Paul carried a string trio composed by his friend Zoltán Székely. Hanging out through the open window he spoke with Kodály. When they came to a stop, Hermann started to whistle a section from the piece. Just before getting off the tram, he impulsively handed Kodály the score. This must have made an impression; shortly thereafter, Székely and Hermann were invited to Kodály's home, started to study with him and it was the beginning of a mutual friendship.

Going abroad

Hermann performed for the first time outside Hungary playing Kodály's Sonata for solo cello during a private concert at Arnold Schönberg's home. This sonata was Hermann's international breakthrough as an interpreter of contemporary music when he performed it at a concert of the International Society for Contemporary Music (iscm).

Hungary went through a turbulent time during the interbellum. Admiral Horthy's reign of terror induced severe anti-Semitism. It is not surprising that so many young musicians left the country. Paul Hermann moved to Berlin to study with cellist and composer Hugo Becker at the Staatliche Akademische Hochschule für Musik, known as an avant-garde breeding ground. The teaching staff, to name only a few included Franz Schreker (who was director) and Paul Hindemith. To earn a living, Hermann gave lessons at a music school, performed regularly and was a member of an early music ensemble.

Even when living in Berlin, Hermann regularly visited his friend and duo partner Zoltán Székely, who had built up a new life in the Netherlands. As a duo they concertized in the Netherlands, Germany and England. Their programs included classical works by Haydn and Mozart alongside contemporary compositions ranging from Rebecca Clarke to Hindemith, Ernst Toch and of course, Kodály and Bartók.

In London, the duo stayed with the Dutch couple De Graaff-Bachiene. Louise Bachiene organized house concerts where young musicians performed. A warm relationship developed between Mr. and Mrs. De Graaff-Bachiene and the two young Hungarians. Jacob de Graaff provided both musicians with excellent instruments enabling them to expand their prospects. A Stradivarius for Székely and a Gagliano for Hermann. Louise urged her niece Ada, who lived in Amersfoort, to attend one of Paul’s concerts when he was in the Netherlands. In October 1929, that opportunity arose when Paul Hermann and Géza Frid toured the Netherlands. Ada and Paul met after a concert and they immediately took to each other.

Paul Hermann's international career was well underway. In the spring of 1930, he was again booked for a series of concerts in England. And in December, he premiered Kodály's Duo for violin and cello at the Concertgebouw, with Székely. The daily Algemeen Handelsblad praised their superior performance: “Two artists with the purest approach and mastery [...] two rhapsodists who seemed to improvise in their perfect, subtle interaction.” That year, Hermann also premiered his own work, the Grand Duo for violin and cello with Székely.

Berlin and Amsterdam

Paul Hermann's friendship with Ada Weevers was lasting; he often visited her family, learned Dutch, and she visited him in Berlin. In February 1931, Paul gave a recital with Géza Frid in the hometown of his new fiancée. The program included Bartók's Rhapsody. The critic in Amersfoort wasn't used to new music: “Perhaps we can digest the numerous ultramodern dissonances better on another occasion.” Paul and Ada were married in Amersfoort on September 29, 1931, and they moved to his apartment in Berlin.

Ada described her first experiences in a long letter to her younger brother, Jaap. The newlyweds couldn't afford to “just go to any concert;” it was too expensive. As an alternative, they listened to concerts on the radio and sometimes attended house concerts. The programs were invariably modern: Hindemith, Stravinsky. Previously this music was performed in concert halls, but now in the absence of sufficient public, in private homes. These concerts often attracted more than a hundred people, and there was a sense of belonging together, everybody shook hands with one another. Ada estimated that Paul knew at least a third of the public, including Hindemith. The young couple soon moved into another apartment in a new, green Berlin neighborhood. Ada wrote to her family: “The stairwell is big enough to move a grand piano, so ... for the time being, we will only buy two beds and two pans for cooking.” Shortly after, they were able to purchase an old Bechstein grand piano.

Hermann continued performing frequently with Székely and Frid in the Netherlands, also in the Concertgebouw. Székely and Hermann played in a recital for the Holland section of iscm at the Amsterdam Conservatory on March 23, 1932. The program included a premiere of the solo violin sonata by Willem Pijper, a solo cello sonata by Bertus van Lier, Ernst Toch's Divertimento and – as now standard practice - two works for violin and cello by Kodály and Bartók. The written press was unanimously enthusiastic. Newspaper Het Volk reported that: “The violinist Zoltán Székely and cellist Paul Hermann, who have both made a second homeland here, are genuine propagandists for our newest music; which, in its development, shows a striking resemblance to the Hungarian school.”

Happiness and tragedy

In the summer of 1932, Ada gave birth to a daugther, Cornelia, in her parent's home in Amersfoort. And Paul was making lots of progress with radio broadcasts in Germany, the Netherlands and England. In January 1933, Hitler seized power as Chancellor. Paul Hermann was of Jewish origin, but had never paid much attention to this aspect. There were many Jews in their artistic circles. It is inevitable that Hitler's anti-Semitic ideas were the topic of the day. The time came to leave Berlin. Certainly Ada's father was very much opposed to anti-Semitism and everything connected to it. He surely recognized the threatening circumstances in Berlin at an early stage. The young family returned to the Netherlands and spent the summer holiday of 1933 at the family summer home in Ouddorp. It was there that life suddenly took a tragic turn. While swimming in the sea, Ada was caught in a gully; she died of a pneumonia in October 1933, only 25 years old. Their baby daughter was lovingly taken care of by Ada’s family. Paul Hermann settled in Brussels to continue his career. From 1933 to 1935 he was part of the Hungarian Gertler quartet; when they performed in Budapest, he visited Kodály and his wife. Hermann wrote to Székely's Dutch wife: “We live here very comfortably, we haven't rehearsed yet, but will start tomorrow. We'll play for the radio on March 1st and on March 7th, and are giving a public performance. [...] I probably will play a “solo” on the radio. [...] I am back in Brussels on March 21st, then I will travel to Amersfoort as soon as possible to see my Bölö [daughter].” Striking is the apparent ease of his flawlessly written Dutch.

Despite his busy international career, Paul Hermann visited the family regularly in Amersfoort from 1933 to 1940. Some of his letters dating from 1935 and 1937 reveal the warm and intense relationships. Moreover, his best friend Zoltán Székely now lived with his wife in Santpoort and he spent the Christmas holidays of 1936 and 1937 with them.

Paris

In 1937, Hermann settled in Paris, where he performed regularly as a soloist. But Dutch musical life remained important to him. On July 20, 1938 he played a concert for the French radio in Paris with a program exclusively of Dutch music (Andriessen, Badings, Hijman, Van Lier, Pijper and Vredenburg). His daughter Corrie remembers his last visit in Amersfoort in August 1939:

That summer he came on my birthday and together we read the recently published book about the elephant Babar. I had just learned to read and he taught me my first French words. A holiday like any other - but I still remember, some vague sense of fear and unrest which prevailed until the end of August 1939, the threat of war becoming acute and suddenly all our relatives from abroad leaving in a hurry. Everyone expected that the Netherlands would remain neutral and that we would meet each other again soon.

In September 1939, war broke out. Contact between the Netherlands and foreign countries became difficult, and later almost impossible. The last news about Paul Hermann appeared in an article about Parisian musical life in the daily Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant of February 1940. Paul Hermann had given an excellent performance of Milhaud's cello concerto. Although he was now a Parisian resident, he still had the Hungarian nationality. When the French began mobilizing, Hermann signed up as a foreign volunteer, in supporting services for the army. He was assigned to a military marching band. Upon German occupation in France, this regiment was demobilized. Paul moved to the southwest of France which was initially not occupied but governed by the Vichy regime. He was safe at the De Graaff-Bachiene's home in Mont-de-Marsan, but city life was calling; he needed to make music and moved into an apartment in Toulouse. With teaching and once in a while a concert, he picked up his daily routine. To stay out of the hands of the Vichy regime, he used false identity papers and was now known as De Cotigny. He thought he was safe, but during a street raid in Toulouse in April 1944, he was arrested and deported to the transit camp Drancy near Paris. His name appears on the transport list of May 15, 1944, from Drancy to Auschwitz, however this train moved on to Kaunas-Reval in Lithuania. Of the more than 800 so-called Arbeitsjuden only a few returned and there is no trace of the others.

Paul Hermann's oeuvre is small; the majority is for strings, well written, with splendid virtuosity for the instruments. In addition to a String Trio from his student days, he composed a Grand Duo, the highlight of his concert programs with his friend Székely. Some piano works date from his Berlin years, and in France he wrote a number of particularly sensitive songs on French poems by Paul Valéry and Arthur Rimbaud. He also composed an orchestral work and a concerto for cello and orchestra. Paul Hermann succeeded in building a bridge between classical and modern idioms; his work is certainly representative of the music from the first half of the twentieth century. Neo-classical in form, based on tonality, while pushing the boundaries. Hermann composed serious music and with lots of depth, and sometimes a light-hearted dance. A certain Hungarian influence is clearly audible, continuing the Kodály-Bartók line.

Sources

Hermann estate

Newspaper archives, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague