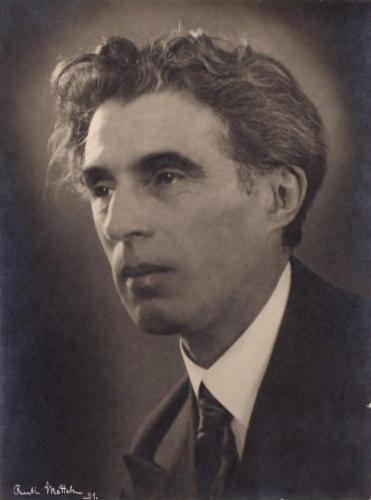

James Simon

James Simon was a highly intelligent and accomplished pianist, composer and musicologist. He studied philosophy, loved poetry and felt at home with the great German musical tradition. Music was his life. So much so, that his son would call him ‘other worldly’. He continued to compose until the very end.

By Phillip Silver and Carine Alders

James Simon was born on 29 September 1880 in Berlin, in a highly assimilated, well-to-do Jewish family. His father being a private banker, the family enjoyed a luxury life. Reading the postcards young James sent home on his holidays, he comes across as a witty teenager. James was the eldest of three siblings. Their parents kept a low political profile, trying to blend in. Their main concern was to educate their children well. In his hometown, James studied piano with Conrad Ansorge and composition with Max Bruch. Like many young and privileged Germans, he studied philosophy at various universities, including Heidelberg and Freiburg. In 1904, he wrote his doctoral thesis on the German composer Abbé Vogler in Munich. Three years later, he married Anna Levy, an equally well-to-do banker’s daughter. Two sons were born: Jörn Martin and Ulrich Ernst.

Being an outstanding pianist, James began his career as a freelance musician. He gave recitals and lectures and sometimes played chamber music. Earning an income was not an issue, both the Simon and Levy family capitals provided for the young family. In an interview with David Bloch, Ulrich remembered how he and his brother would go to their father’s recitals in the Beethoven Salle. He also remembered how his parents would always quarrel. While James was devoted to German classics, Anna was more adventurous and would have liked him to be more like Hindemith or Schoenberg. ‘He was very German, really. For me he became the great guard of the German classical repertoire, especially Bach and Mozart’, said Ulrich. From 1907 to 1919, James taught at the Klindworth-Scharwenka Conservatory, where he came to know colleagues like cellists Marix Loevensohn and Daniel Hofmekler. Although not dated, he must have composed his Cello Sonata during these years. It was published by Friedrich Hofmeister in Leipzig. His other compositions from this period – mostly songs and chamber music – were published with various publishers in Berlin.

Financial crisis

Unlike many young Germans, including his brothers-in-law, James never had to serve in the army – we don’t know why. After the First World War however, the family capital had vaporized. All was lost and Anna had to keep the family alive with potatoes – if she could find any. James would teach an American pupil for one dollar per lesson. It barely bought some groceries. He also taught his niece Rosa, so that his sister Berta and her husband could help with some extra money. In the post war years, James started to compose more seriously. He would get up at 7 am every morning, working at his desk. As a musicologist, he would also write articles for magazines like the left-wing weekly Die Weltbühne. One of the major compositions he was working on was the opera Frau im Stein. It premiered in Stuttgart in 1925 and was a great success. However, that same night, president Friedrich Ebert died and there was no room for reviews in the newspapers. By that time, the family’s financial situation had improved a bit. James and Anna would host ‘domestic improvisations’ to add to their income. The audience consisted of more fortunate acquaintances, no programs were given in advance. Ulrich remembered how his father would present the finale of the second act of Mozart’s Figaro, singing all the different parts and playing the orchestral parts on the piano. Despite their rows, Anna and James would work together as well. Anna helped him prepare Rainer Maria Rilke’s text for Ein Pilgermorgen, a cantata composed in 1930.

When the Nazi’s came to power in 1933, the Simon family dispersed. Jörn followed his communist ideals and went to Russia. Anna moved to Paris where she trained to become a beautician. She once visited her son in Moscow, who soon after disappeared in Stalin’s Great Purge. Ulrich fell in love and built a new life for himself in England. James went to Zurich, but in October 1933 he joined Anna after she settled in Amsterdam. The couple had separated by then, but there was no official divorce. James had formed a new liaison with Toni Therese Werner. Toni was married to Hans Appelbaum, who owned a chocolate factory. When the Nazi’s took control over the factory in 1936, the Appelbaums fled to the United States. Where and how Toni and James met is not known, but they stayed in contact until his death and James would dedicate around fifty songs to her.

The Amsterdam years

Immediately after his arrival in Amsterdam, James started to perform for the Dutch VARA Radio in Hilversum. He would perform Chopin – one of his favorite composers – but also his own works. From letters to Toni, we know that James Simon performed Chopin in a hurry, afraid of missing the last train to Amsterdam. He continued his life of recitals, lectures, teaching and composing. Within weeks, the first advertisement appeared in the newspapers to announce piano lessons and lessons in music theory. He had plenty of pupils, organized house concerts and gave recitals in Amsterdam and The Hague. He performed with fellow refugees like Arved Kurtz (Simon’s violin sonata), but soon also found Dutch musicians to perform his music. Soprano To van der Sluys and alto Annie Woud performed his songs and clarinetist Johan van Hell and oboist Leo van der Lek (both musicians in the Concertgebouw Orchestra) performed his chamber music. Cellist Marix Loevensohn, his colleague from Berlin and now solo cellist with the Concertgebouw Orchestra, premiered Simon’s Ahasver for cello and orchestra in Haarlem in December 1934. The Concertgebouw Orchestra was about to program his Symphonic Dances when the war broke out. His lectures (in German) were well appreciated and in the Dutch magazine De Wereld der Muziek (The World of Music) Simon published several articles. His name appears in announcements for many concerts and lectures for Jewish refugees as well. Late in 1938, he visited his brother-in-law Martin Seligsohn in Palestine. His sister Berta had died in February that year. Lamento in Jemenitischer Weise was composed on 17/18 December 1938 to honor her memory. He dedicated the music “Meinem lieber Martin!”. James gave concerts and lectures in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Together with his former colleague Hofmekler, who emigrated to Palestine in 1933 and had started the conservatory in Tel Aviv, he performed his Cello Sonata for the Palestinian Radio. On 26 January 1941, Simon’s sixtieth birthday was celebrated during a concert organized by the Nederlandsche Vereeniging voor Hedendaagsche Muziek (Dutch Association for Contemporary Music). The program included several compositions by James Simon. With violinist Alma Rosé he performed at Het Apeldoornsche Bosch, a Jewish institution for the mentally ill in August 1941. By then, Jewish musicians were no longer allowed to perform in public.

European at heart

Although he had several opportunities to emigrate, James Simon decided to stay in Amsterdam. From Paris, Ulrich sent a telegram to his father in Palestine, advising him urgently to stay there and go underground. But he didn’t, James Simon was not the sort of person who would find a job or go underground, he was a musician. Anna was angry when he came back. There was an option to go to the United States thanks to an affidavit from a certain Mr. Greenberg, who saved over 70 Jews in this way. Not James. According to his son he would never feel at home in a non-German speaking country. James Simon was a European at heart. Not even Toni – who had left her husband and lived with her brother – could persuade him to come to the States. On 14th June 1939 James wrote to Toni: ‘You, music and nature: those are the bright realities of my life. [...] Because we – as you correctly state – unfortunately only read horrible things in the newspapers (and one hears horrible things that do not even make the newspaper) , more than ever I need to focus on what is most valuable. Libraries and the little known Kupferstichkabinett become my mental islands. I read the Vorsokratiker, I listened to Hubermann on 16 May (heavenly substance), listened to Cosí as Busch record with my friends in Bloemendaal and on 21 June I will hear Bach in Amsterdam’s Oude Kerk. Why are you not beside me? Try and influence all things political so that “Mein Kampf” becomes “Mein Niederlage”.’ The song enclosed in the letter is Ich Schlaf, ich traume on words by Paul Fleming. Between 1932 and 1943, James Simon sends almost fifty songs to Toni. Six of them were published by Broekmans & Van Poppel in Amsterdam.

Terezin

Early 1942, Anna managed to leave Amsterdam, she survived the war in Switzerland. According to the Amsterdam City Archives, James moved to his last address in Amsterdam on 28 January 1944, Weesperplein 1. Until recently, this had been the Jewish hospital in Amsterdam, but on 13 March 1943, all patients and staff were taken away and sent to Sobibor. The empty building was used as a general hospital afterwards. In the early spring of 1944, James Simon was sent to Westerbork, the Dutch transit camp. On 4 April 1944 he was forced to join a group “Juden mit Verdiensten um das Reich und sonstigen Zivilverdiensten” that was transported to Terezin. In the list he is described as “Bekannter Berliner Pianist”. In Terezin, like many others, he continued to compose, perform and give lectures. Between his arrival in early April until his transport to Auschwitz on 12 October that year, Simon gave 13 lectures in the camp. He started with his lecture ‘Faust in der Music’, which had been published in a series edited by Richard Strauss in December 1906. He further talked about Bach, Händel, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Schumann. His final lecture in September dealt with the subject of humor in music. On 9 July 1944, his Psalm 126 premiered. It would be performed by Karol Fischer’s Durra Choir seven times. On 12 October 1944, he was transported to Auschwitz. A witness remembers how the composer, seemingly unaware of what happened around him, sat on his suitcase, waiting for the train and jotting down his last musical thoughts.

Music

James Simon composed in all traditional forms including solo instrumental, chamber music, lieder, orchestral, liturgical and operatic. A prolific composer he notedly gravitated to the composition of lieder of which there are more than one hundred. Considering the number of his works that have survived and been located, it is saddening to note just how few of them were published during his lifetime. The works that were published are long out of print, and the greatest percentage of his music remains in manuscript, divided among libraries and institutions such as the British Library in London, the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City.

Among his works there are several whose titles were referenced in 1930s and 40s newspaper notices but have thus far resisted all attempts to locate them. The wide dispersal of his manuscripts have made it difficult to present a complete listing of his works though progress, it must be noted, has taken place over the past several years.

As a composer James Simon embraced a late Romantic language that would not have been out of place if used half a century earlier. More than occasionally passages appear that show a relationship to the music of Richard Strauss and Edvard Grieg. And yet these works possess and retain relevance due to skillful writing and an emotional presentation that eschews displays of artificial sentiment.

The innate conservatism of Simon’s musical language did not close him off from contemporary influences. The Lamento für Cello und piano (in Jemenitischer Weise) was composed upon the death of his sister in 1938 in Tel Aviv. What is highly probable is that this is a work influenced by the contemporary efforts of Paul Ben-Haim to synthesize a musical language that could accommodate both Western and Middle Eastern elements. Simon’s efforts result in a successful and moving hybrid, certainly unique among his other output.

Simon was essentially a miniaturist and this is evident in both small scale compositions such as his lieder or works for solo piano, and in his larger scale works such as the Sonata for Cello and Piano or the Sextet for Piano and Winds in which a compact brevity is evinced in the individual movements. One is reminded of Polonius’s admonition in Hamlet that “brevity is the soul of wit.” Simon does not wear out his welcome in these extended compositions.

Sources

Interview with Prof. Ulrich Simon by David Bloch, 6 February 1996 (transcribed by Joseph Toltz). Part of the David Bloch Archive at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Newspaper archives Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague

Amsterdam City Archives

Guide to the James Simon collection 1931-1945 AR5930. Processed by Julie Dawson - Leo Back Institute, Center for Jewish History New York.

Biography written by David Bloch: http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/theresienstadt/simon-james/

James Simon manuscripts in the British Library: Simon Music Manuscripts Add MS 62117-62120