Dick Kattenburg

Dick Kattenburg was extremely talented. It was obvious that he would enjoy a flourishing career as a violinist for years to come. Even today, some seventy years later, his appealing music immediately touches the heart. A large part of his oeuvre was created during his period in hiding. He was murdered at the age of 24. Thanks to his romance with a young flutist, his manuscripts were preserved and found an audience after all these years.

by Carine Alders

Jazzy melodies by a promising talent

Dick Kattenburg was born in Amsterdam on November 11, 1919, the second child of Louis and Heleen Kattenburg. He had an older sister Daisy, and brother Tom was born in 1922. Great grandfather Levie and his ten sons had laid the foundations for a textile empire that would be successful for future generations. Dick's father was employed by the Hollandia-Kattenburg factory owned by his cousin Jacques and he was supervisor in a second family business. The young affluent family moved from the big city to Bussum, a town in the countryside. Dick was an ordinary child; he won a prize for a coloring page, sent a story about his dog Bobbie to the local newspaper and went to high school in Bussum. He was an ordinary child with an unusual musical talent.

Composer Hugo Godron, teacher at the music school in Bussum, gave Dick his first violin lessons, and mentored him in his first steps as a composer. In a child’s handwriting, the Valse d'amour is clearly one of his earliest works. The first works with an official opus number, the andante for string quartet and two Hebrew songs, have probably been lost. After high school, Dick probably enrolled at the Collège Musical Belge, a private music school in Antwerp. At the age of 17, he obtained his music theory and violin diplomas. Tap Dance, a piece for four-handed piano and tap dancer, dates from this time.

In love

With a degree and his first compositions completed, the young composer returned to the Netherlands. His brother Tom's address, Bloemgracht, Amsterdam, is noted in the margin of a music manuscript. Dick, no doubt, was often in his hometown. He met Ima van Esso, who studied flute at the Amsterdam Music Lyceum. She also came from a well-to-do Jewish family. At their home in the southern district of Amsterdam her parents organized house concerts, and possibly Dick was present, too.

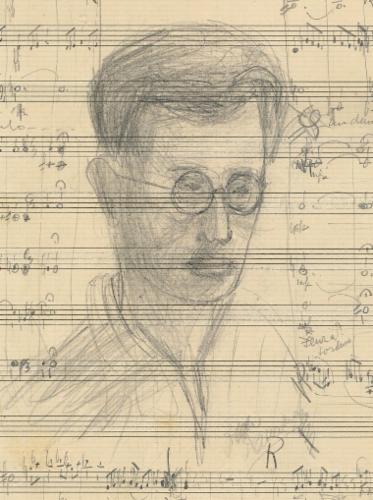

In May 1937, he dedicated his Sonata for flute and piano to Ima and gave her the handwritten manuscript. That same year he worked on a four part Divertimento for wind quintet. Only a comprehensive set of sketches exists of this piece. These reveal Dick's passion for drawing: scribbled between the staves are several portraits, most likely composers. Even a large self-portrait can be found on one of the pages. In March and April 1938, Dick Kattenburg composed the Escapades pour deux violons and dedicated its first movement to his friend Theo Kroeze. The second movement “Andante con amore” is dedicated to a certain Mies. A drawing of heart and arrow gives a clear understanding about the message of this dedication.

House concert

The daily Gooi en Eemlander of December 19, 1938, published a review of a concert at Hugo Godron's home. With violinist Dick Kattenburg and Theo Kroeze on viola, they played Mozart's flute concerto in a chamber music arrangement. At this concert, a string trio by one of “Godron's advanced composition students,” Dick Kattenburg, had been performed for the first time and according to the critic it was: “A fairly compact piece showing remarkable mastery and a very personal style; looking forward with great interest to his further development.” Fortunately, this work has been preserved. A remarkable ink and watercolor drawing adorns the cover page, dated 1938 and depicting the three musicians: right Dick Kattenburg, center Theo Kroeze and left cellist Anton Dresden, who later became conductor of Toonkunst Bussum Choir and Orchestra.

Dark clouds

The score of the string trio is signed with the pseudonym “Van Assendelft Van Wijk," and on the back cover, between some small sketches, is a portrait of Hitler and sketch of a soldier giving a Hitler salute. To what extent were these young musicians aware of the dark times ahead? Despite the threat of war, Dick continued writing cheerful and catchy music, and, fitting for an adolescent, he was involved in amorous adventures. In January 1939, he composed Flirtations, for four-handed piano and on June 8, 1939, he completed Pièce pour flûte et piano, another work written for Ima van Esso. In the fall, Dick planned to complete his violin studies at the École Normale in Paris with a student of the revolutionary violin pedagogue, Lucien Capet. That never happened. After the summer he started working on his Quartet for flute, violin, cello and piano, in three movements, which would occupy him for more than a year. One month after the German invasion he composed Lied ohne Worte in honor of his mother's fiftieth birthday. This was their last summer together as a family. Father Louis died in September 1940. Soon after the first anti-Jewish measures came into effect. In January 1941, Dick's sister Daisy left home to get married and at the same time all Jews were required to register.

However, Dick succeeded in passing the state music theory and violin exams in The Hague, under Willem Pijper's guidance. In an advertisement in The Jewish Weekly of September 5, 1941, he announces his parents' home address as his teaching location for violin and music theory. He continued composing, started on a violin sonata and wrote a Novelette for piano, dedicated to his second cousin Rita Kattenburg, a piano teacher; they frequently played together. Meanwhile, the Aryanization of the Dutch music world was in full swing. As of May 1942, all Jews had to wear a yellow star; signs “Forbidden for Jews," appeared everywhere. Soon thereafter, the deportations began, followed by raids because too few people came forward. His brother Tom and mother Heleen went hiding in Deventer. Heleen found refuge with the family Oostergo; Tom was taken in by the Bennekers family. It seems that Dick first moved to Amsterdam and later also went underground.

Jewish identity

The confrontation with his Jewish origin, triggered his immersion in Judaic cultural heritage. He began arranging Hebrew melodies, denoting them as Palestinian, Romanian or even Mexican. The manuscript titles were written in Hebrew; dating was sometimes based on the Jewish calendar. Some musical signs i.e. “segno” were replaced by a Star of David. The movements of a suite for violin and piano were now entitled “Nigun” and “A Redl.” He started signing his compositions under pseudonyms like CJ van Assendelft van Wijck and KvD, alias K. van Drunen or K. van Dunsen. At that time, there actually lived a Jacob Cornelis van Assendelft van Wijck in Amsterdam, a modest chimney sweep with a fancy name. It is not known whether there was a connection between him and the Kattenburg family. He often signed with the initials KvD; what it stands for remains unknown to date. Kattenburg removed his name from all earlier compositions.

Leo Smit

Although most of the music we know by Dick Kattenburg is mainly chamber music, some manuscripts reveal that in the summer of 1942 he focused on instrumentation and orchestration. He took private lessons with Leo Smit, who taught privately at his home at the Eendrachtstraat in Amsterdam. Soon those meetings became too dangerous and lessons continued through correspondence. Dick concentrated on orchestrating Horras (Jewish dances) from Solomon Rosowski's book. A street plan of Amsterdam is drawn on a manuscript dated September 22, 1942, but Dick Kattenburg’s underground address at that time is unknown.

An undated letter addressed to Leo Smit:

I apologize for my poor handwriting, but my paper and pencil are of deplorable quality and copying the whole thing seemed to be a waste of paper and effort, and I'd first like to know what is right and what isn't . [...] I sincerely hope to resume the lessons at your home, but I fear I have to accept this substitute for a long time to come (although excellent in content, the delivery takes forever). Apologies for this “silly letter,” cordial greetings to your wife and wishing you good luck, your “student.”

These lessons consisted of manuscripts that were sent back and forth - probably by a resistance courier - with notes like “cello and bass sound emphatic enough, trombone like a bull in the Chinese shop” (Leo Smit) and “I hope you will not be angry if I don't accept your assertions, and that I seem to contradict your arguments” (Dick Kattenburg). The two composers would never see each other again.

Utrecht

At a certain point, Dick Kattenburg went underground in Utrecht at the home of a friend, pianist Ytia Walburg Schmidt. A rough draft of his Romanian Folk Melodies for Violin and Piano, dated December 1942 and signed “KvD,” is dedicated to “YCWS,” and suggests that he was in Utrecht around that time. After the war another friend, Theo Kroeze, told how he took Dick, disguised as a bricklayer (“a ridiculous sight with his Jewish face and habit”) to a hiding place on the Nachtegaalstraat. Whether in hiding or not, Dick continued composing. The cadenzas he wrote for the Beethoven and Mozart violin concertos, prove that the violin kept him busy. In August 1943, he finished a virtuoso Rhapsody for solo violin. And he started the outlines for a sonata for viola and piano, the first movement completed in Utrecht on February 27, 1944.

His hiding place was betrayed and Dick wandered from one temporary shelter to another. According to the Red Cross, his last known address was the Uiterwaardenstraat 387 in Amsterdam. He was finally arrested, possibly during a raid in a movie theater. On May 8, 1944, he managed to send a note from Westerbork to his aunt and uncle in Amsterdam. Within two weeks he was transported to Auschwitz. His death certificate states that he died on September 30th somewhere in Central Europe. He probably died prior to the arrival of the liberators, when the surviving captives were chased during the ‘death marches.’

Optimistic romantic

Many of Dick Kattenburg’s compositions breathe an optimism of the new era, but are also downright romantic. He imbued jazz rhythms and polytonality, French music (Ravel) and Stravinsky's Neoclassicism in several of his works. Captivating, lyrical melodies (his trademark) are often interspersed with energetic rhythmical passages. The Quartet for flute, violin, cello and piano is the most substantial chamber work of Kattenburg's legacy.

To a classical sonata form, he adds jazz elements, surprising harmonies and upbeat music hall sounds, binds it together with strong melodic lines, sometimes reminiscent of Negro spirituals. In his two works for flute and piano, both with a romantic and humorous touch, a jazz idiom plays an important role. Characteristic of all his works is the extraordinary melodic expressiveness, best exemplified in the unfinished viola sonata written in 1944. Ima van Esso carefully preserved Dick’s flute sonate all her life, but never played it. The music finally came to life when she donated this treasured manuscript to flutist Eleonore Pameijer.

Sources

Archives Dick Kattenburg (Netherlands Music Institute, The Hague)

Micheels, Pauline et al. Wat bleef was hun muziek – 10 jaar Leo Smit Stichting (The Hague, 2007)

Micheels, Pauline, ‘Regenjassen en oorlogsleed; Amsterdamse ondernemers, Jacques N. Kattenburg’ in: Ons Amsterdam (March 2009)

Vries, Wim de, ‘Wij waren met meer’ op www.joodsecomponisten.nl

Newspaper archives Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague