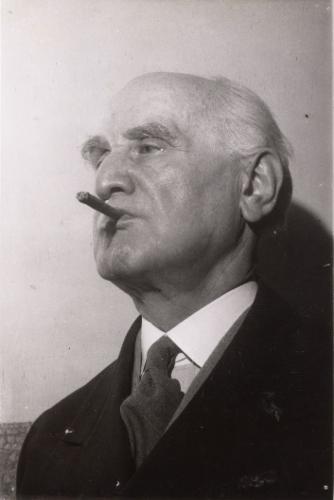

Sem Dresden

Despite his German-oriented teachers, Sem Dresden felt attracted early on to modern French music. He developed his own refined and sober style, composing his entire life. Dresden was of pivotal importance to Dutch musical life, working as a choral conductor and director of the conservatories in Amsterdam and The Hague. His legendary composition classes had a major impact during the interwar period.

by Geert van den Dungen

A pragmatic idealist

Sem Dresden was born into an Ashkenazi Jewish family originating from the Prussian town of Gdansk, today a city in Poland. Both his father and grandfather were diamond workers in Amsterdam. His father Marcus later developed into a successful broker in that industry, and had close contacts with Henri Polak, founder of the Dutch Diamond Workers' Union. Although a member of the Dutch-Jewish religious community, the Dresden family was influenced by the increasing secularization, which began in the nineteenth century through social integration and assimilation. Certain Jewish rituals and holidays were not ignored, but only celebrated within the family circle.

In Sem Dresden’s family home was a piano. His father sang in a diamond workers' choir, The United Singers, and was chairman of its board for several years. Its conductor Maurice Hageman, gave Sem his first violin and piano lessons at the age of six, and his father took him to the choir rehearsals. A few years later he took violin lessons with J.C. Dudok sr. and Felice Togni, a member of the Concertgebouw Orchestra. At twelve, Sem joined the Amstels Brass Band, with mainly Jewish musicians, and under the direction of David King jr. Sem played the trumpet and timpani. Already as a youngster his appetite for music was insatiable. He wanted to become a professional musician but his father had other plans for him. Sem effortlessly completed high school, and at age sixteen also obtained a diploma from the Public Business School. He worked for some time in an office, although very reluctantly and finally, despite paternal protests, chose for his passion: music.

Following his heart

In an eight month period, he learned all about music theory with Frederik Roeske, who introduced him to Bernard Zweers, composition teacher at the Amsterdam Conservatory. Zweers recognizing Sem's extraordinary musical talents, became his composition teacher. In this early period (1901-1903) Sem composed several songs for voice and piano, some piano pieces and a piano trio; all in the late-Romantic German style like his teachers Roeske and Zweers.

His interest in vocal music was significantly fueled by his love for Jacoba Dhont, a young singer from Middelburg who studied with the opera singer Cornelie van Zanten in Amsterdam. Van Zanten was founder of the Meisterschule für Kunstgesang in Berlin, and once Jacoba obtained her conservatory diploma, she followed her teacher to Berlin. And Sem Dresden followed his love. In September 1903, he grabbed the chance to study orchestral conducting and composition with Hans Pfitzner at the Stern Conservatory in Berlin. Pfitzner was not a typical late-Romantic German. On the contrary, he was the opposite of Richard Strauss and for that reason he was nicknamed the “German Debussy.” Sem and Jacoba had two very happy years in Berlin. They fully enjoyed Berlin's dynamic musical life and Sem learned a great deal from Pfitzner about orchestral conducting and opera. He continued composing songs and chamber music, including a sonata for violin and piano, and Thema und Variationen for violin, piano and cello. Pfitzner encouraged him to incorporate sobriety and sophistication into his music, especially by studying the ancient polyphonic masters of the Renaissance.

Beloved conductor

After their return from Berlin in the summer of 1905, Sem and Johanna, now engaged, quickly developed their musical careers. In that same year, the first works by Sem Dresden were published by the firm A.A. Noske in Middelburg: six songs for voice and piano. That was an important incentive for the young composer. In September, he was appointed director of the Tiel Singing Society and the Tiel Men's Choir, and in that town he also gave weekly violin, piano and theory lessons. He was a respected and beloved conductor, showing his natural leadership up until 1914 when he finally said farewell to Tiel and both choirs. In the years 1909-1912, Dresden also managed the newly established Department of Music in Laren.

Dresden was eager to work with professional singers and begin an a cappella choir, like Daniel de Lange and Anton Averkamp before him. The Dresden's numerous contacts with musicians and vocalists in Amsterdam led to the establishment of the Madrigal Society in 1914. Alphons Diepenbrock organized the fundraising, allowing the new society to rehearse and develop for an entire year without the obligation of public performances. Twelve years of great success followed, with performances of Renaissance polyphonic works and contemporary choral music. And then Dresden conducted the much larger Haarlem Motet- and Madrigal Society for another twelve years. Both choirs received unanimously wide acclaim for their tonal quality and strong sense of style.

A legendary composition class

In 1917, Dresden began teaching at the Amsterdam Conservatory: counterpoint, harmony, analysis and composition. He succeeded Julius Röntgen in 1924 as the director of the conservatory. His task was to modernize this institution in every way, educationally and organizationally. He was one of the initiators of the new conservatory building on the Bachstraat. Dresden convincingly presented his progressive ideas; likewise he showed a personal interest in his students and was capable of conveying his great skills. As a music pedagogue, he made his mark on generations of musicians.

His composition class was legendary and welcomed not only composition students, but also instrumentalists and theorists, all of them encouraged to discuss their work. During these lessons, Dresden handled issues of harmony, counterpoint and form, and suggested practical solutions for instrumentation and orchestration, but never imposing his artistic views on the students. Dresden's composition class included Jacques Beers, Jan Felderhof, Cor de Groot, Marius Monnikendam, Jan Mul, Jan Nieland, Leo Smit and Rosy Wertheim, among others.Famous conductors like Eduard van Beinum, Hein Jordans, Willem van Otterloo and Frits Schuurman had all been Dresden's students. In 1937, he succeeded Johan Wagenaar as director of the Royal Conservatory in The Hague, which also underwent, under his direction, a reorganization.

New sounds

His creative oeuvre, consisting of some 160 works, developed steadily. He began around 1900, and worked until the end of his life. His former pupil Jan Mul, completed the instrumentation of Dresden's last work, the opera François Villon (1956-1957). His conservatory years, tween 1924 and 1940 were the least productive; he led a hectic life as director, leaving very little time for composing. Remarkably, none of his German oriented teachers - Roeske, Zweers and Pfitzner – had a lasting influence on his music. Apparently, his musical personality was too outspoken. Pretty soon, his affinity with the music of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss disappeared. Like his contemporaries Jan Ingenhoven, Daniel Ruyneman, Matthijs Vermeulen and the slightly younger Willem Pijper, he was increasingly drawn to the modern trends in French music. Already before World War I, Dresden focused on the new sounds of Gabriel Fauré, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel. He developed his idiom mainly within neoclassical form structures. Characteristics are his clear melodic lines, sophisticated and varied rhythms and metrics, and innovative harmonies. He pursued an austere, almost introverted sound. Successful early examples include the Sonata No. 1 for cello and piano (1916) and the Sonata for flute and harp (1917), both published by Maurice Senart in Paris. There was international interest for this last work, written in a style reminiscent of Debussy.

Sem Dresden was a humane, thoughtful and analytical thinker with a witty and optimistic character. According to Marius Flothuis “his multifaceted personality is reflected in his work.” Flothuis recalled in this context the Vocalises for soprano and seven instruments (1935) and the Sinfonietta for clarinet and orchestra (1938) as “examples of an ingenious and sophisticated interplay - performed at such a high level that it wouldn't be right to qualify them as 'academic'.” This term, suggesting a lack of emotional content, was sometimes used to describe Dresden's music. In fact it ignores the subtle emotions present under the surface of his music. In later compositions, he directly exposed such emotions, e.g. his award-winning Dansflitsen (Dance Flashes), an orchestral work composed in 1951.

Quiet resistance

In September 1935, Sem Dresden already appeared on the Reichskulturkammer's list offorbidden composers in Nazi Germany. He was the only Dutchman among illustrious names like Antheil, Berg, Bloch, Casella, Copland, Eisler, Krenek, Satie and Weill. After the outbreak of World War II, Dresden, as director of the Royal Conservatory in The Hague was confronted with the measures implemented by the Germans. In September 1940, the Royal Conservatory had to be renamed into the National Conservatory. And two months later, all Jewish teachers, Rosa Spier (harp), David Meijer (bassoon), Lothar Wallerstein (opera class) and Dresden himself, were suspended from their duties. The composer Henk Badings succeeded Dresden in 1941 as director, but remained committed to the Dresdens' well-being during the war. As of April 1, 1943, the education department forced Mrs. Dresden-Dhont to resign as solo singing teacher. This in regard to a regulation of the German occupying forces to remove all civil servants who were married to Jews. Apparently, this resignation had been repeatedly suspended by Badings' interference. Badings also managed to arrange that Dresden was relieved of his duty digging anti-tank ditches.

The couple Dresden-Dhont, who were a “mixed marriaged,” moved in December 1940 to villa De Pauwhof in Wassenaar, a refuge for intellectuals and artists, but also a shelter for people in hiding. They remained in Wassenaar until the end of the war.

Sources

Dresden, Sem: Het muziekleven in Nederland sinds 1880 (Amsterdam, 1923)

Dresden, Sem: Stromingen en tegenstromingen in de muziek (Haarlem, 1953)

Hiu, Pay-Uun & van der Klis, Jolande (red.) Het Honderd Componisten boek: Nederlandse muziek van Albicastro tot Zweers (Haarlem, 1997)

Kasander, John, 150 jaar Koninklijk Conservatorium. Grepen uit de geschiedenis (Den Haag, z.j.]

Overbeeke, Emanuel & Leo Samama (red.), Entartete Musik, Verboden muziek onder het nazi-bewind (Amsterdam, 2004)

Sanders, Paul F., Moderne Nederlandsche componisten (Den Haag, z.j.)

Samama, Leo, Nederlandse muziek in de 20-ste eeuw (Amsterdam, 2006)

Zoeren, Elbert van, De Muziekuitgeverij A.A. Noske (1896-1926), Een bijdrage tot dertig jaar Nederlandse muziekgeschiedenis (Haarlemmerliede, 1987)