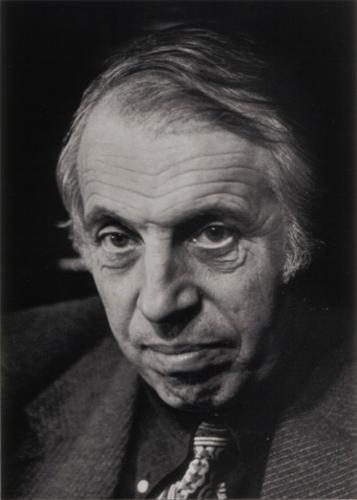

Lex van Delden

During World War II, Alexander Zwaap had to cover his identity by living under an alias. As of 1953, he legally changed his name to Lex van Delden. His life story is impressive considering the traumatic events he experienced in the war years. A past of which he never spoke, and which he knew to overcome with tremendous courage and resilience. Music was for him a “transfer medium between people.” He literally practiced this with his compositions. Van Delden was a great advocate of Dutch music and held several board positions in the Dutch music world.

by Margaret Krill

Keen journalist, but above all a composer

Lex van Delden was born on September 10, 1919, in Amsterdam's Jewish quarter, on the Recht Boomssloot. His parents, Wolf and Sarah Zwaap, shared a house with his grandparents. The family was not orthodox Jewish. As a youngster, he loved playing for the local Ajax Football Club. Even during his medical studies, football remained an intrinsic part of his life. He never missed a game of the club competition and was a regular in the Ajax boardroom. In the 1960s he wrote for newspaper Het Parool a weekly column about football: “From the stands, from the fields.”

Van Delden's father was a teacher at a Jewish school and had worked with a colleague on operettas for children. He also played a bit of violin, but there wasn't much music making at home, although the family regularly went to the Volksconcerten (concerts to elevate the workers). At the age of seven Lex started piano lessons; later on with pianist Cor de Groot, only five years his senior and already a rising star. Once while bedridden, he began jotting down some notes. It was a pleasant way to pass the time. At sixteen, he had a part-time job as an accompanist for the ballet. Just for fun; his dream was to become a neurosurgeon. In 1938, he enrolled at the Municipal University of Amsterdam. The student orchestra was led by Nico Richter, fellow medical student and composer. Richter soon asked Van Delden to compose something for the orchestra. This resulted in Liederen (songs) for voice and small orchestra. Van Delden considered this work as his opus number one, even though he had already completed dozens of compositions. During the performance in February 1940, Van Delden was a member of the orchestra, dressed in military attire; since the mobilization, he had become a reserve officer of health.

Traumatic war years

As a Jew, Van Delden was forced to give up his studies in 1942. His only choice was to go into hiding. A shelter was arranged at the home of a former colleague of his father, now headmaster at the penitentiary in Veenhuizen, because there were no German soldiers in the area. Shortly afterwards, his parents who were also in hiding, were betrayed and deported to Sobibor. Van Delden never saw them again. It was only in 1980, when he laid eyes on their postcard written to him from the Hollandse Schouwburg while awaiting their transport to the camp.

The war years were strenuous; locked up in a room, unable to make any noise which, of course meant no piano playing, and at night, hiding under the raised floor of a basement closet. Van Delden fell into a depression and his hosts eventually included him in their daily family life. He survived by translating all kinds of literary works and he helped their daughter with her homework. At one time, through a contact with the student resistance movement, he was sent to the province of Brabant, where he forged identity papers at the Personal Identification Card Centre. On a daily basis he visited, by bicycle, a family with a piano and even managed to give house concerts. Around this time, he suffered complete loss of vision in one eye due to an explosion of a carbide lamp. Immediately he knew it was now impossible to become a neurosurgeon. In early 1944, a college friend, one of the leaders of the Amsterdam Student Group, encouraged Van Delden to return to Amsterdam to join their resistance movement. Back in Amsterdam, he was confronted with the reality of being an orphan and that his parental home was ransacked. Disoriented and desperate he had to resume his life, and thanks to all his talents, it went astonishingly faster than expected.

A music critic

Van Delden got involved with the dance company “Op Vrije Voeten” (on Free Feet), whose members had not been affiliated with the Kultuurkamer (a regulatory cultural agency installed by the German occupying forces during World War II). The group performed several times in Amsterdam's City Theatre (Stadsschouwburg) in August 1945, where a work by Van Delden was also heard. This was followed by more performances and the chance of making a tour through France. Pursuing a career in music was the next logical step. But Van Delden first wanted to study instead of performing. Due to lack of funds, however, attending a conservatory was out of the question and so Van Delden remained primarily a self-made man. Paul F. Sanders, a well-known Dutch journalist, after hearing Van Delden's music for ballet, invited him to become a music critic for the daily Het Parool. In those days, critics were often composers. After his retirement in 1982, Van Delden remarked that in the post war period, critiques focused on the music much more so than on its performance.

Shortly after the war, he married Jetty van Dijk, sister of the actor Ko van Dijk. Their son Lex van Delden jr. would later follow in the footsteps of his famous uncle. Meanwhile, Van Delden continued composing; in 1948, he was awarded the Music Prize of the City of Amsterdam for his composition Rubáiyát, which also received excellent international reviews. And so his dual career took off. In 1951, Van Delden was appointed chief editor of arts and music for the daily Het Parool, a position he fulfilled with heart and soul. He had developed into a journalist par excellence. But not everyone could appreciate his sharp pen.

Free from the French tradition

The musical climate was favorable for Dutch musicians and composers after World War II and Van Delden music was performed frequently, thanks to the many commissions he received from musicians. In the early 1950s, countless reviews appeared of performances of his work in England, Germany, Sweden, Prague, Brazil and North and South America. His compositions were received enthusiastically, especially abroad, which was not always the case in the Netherlands.

As a composer Van Delden was self-taught and he developed his own style. In 1953, composer Matthijs Vermeulen reviewed Van Delden’s Sonata per Pianoforte (1949) very positively. Vermeulen felt that Van Delden as a composer was freed from Willem Pijper and Debussy. He even thought that Van Delden was capable of composing an opera that would last in the repertoire. In the late 1980s, Van Delden expressed that the period around 1940, when he worked intensively with the singer Hendrik Lindt and Nico Richter, had been of crucial importance in his development as composer. Initially his compositions were full of French influences, but these gradually disappeared and he intuitively followed his own compositional path.

Van Delden certainly didn’t belong to the avant-garde movement. In the 1960s, he openly opposed the Notenkrakers, (Nutcrackers) a movement of young Dutch musicians protesting against the music establishment. This labeled him as a conservative composer, and it earned him several enemies among fellow composers. Rumors circulated that his music had vanished from the repertoire because it was old-fashioned. However, he sat on the board of GeNeCo (Association of Dutch Composers) with some of these modernists, and even served as its secretary and president for some time. Only a few of his opponents would later confess that Van Delden was indeed important for the Dutch music culture.

From 1944 until shortly before his death, despite his hectic journalistic and managerial activities, he continued working on a large and varied oeuvre exceeding one hundred compositions. In addition to ballet and theatre music, his chamber works are significant for their unusual instrumentation. He also wrote many songs and choral music. Most noticeable are some ten works for harp, of which the Harp Concerto (1951/'52) and the Impromptu (1955; for harp solo) were awarded two First Prizes by the Northern California Harpists' Association. Van Delden was considered an outstanding craftsman, but he only realized himself how he composed when he made an analysis of a sextet in 1983 that he had written for the Gemini Ensemble: “....yet again, a matter of spontaneous ideas, guided by intuition and self-criticism.”

In his music, Lex van Delden expressed his deeply felt social concerns. In Memoriam for orchestra was his reaction to the flood disaster of 1953. The oratorio De Vogel Vrijheid (The Bird Freedom, 1955) is a passionate protest against slavery. In the turbulent 1960s, his radiophonic oratorio Icarus was written to “protest against costly aerospace programs, when loads of money is blasted into outer space, while on earth widespread poverty and deprivation prevails.”

Advocate of Dutch music

In the 1960s, Van Delden's music was programmed annually by five or six Dutch orchestras but he still criticized their programs. In his opinion, Dutch composers as well as Dutch musicians were underrepresented at the major venues. His commitment to the promotion of Dutch music led to several managerial positions, including the Society of Dutch Composers (GeNeCo), the Dutch chapter of the iscm, the Eduard van Beinum Foundation, the Amsterdamse Kunstraad, Donemus Publishing and Buma/Stemra, the copyrights organization for music authors and publishers in the Netherlands. Moreover, he fought to strengthen the social-economic position of Dutch composers. He was a jury member of the Zilveren Vriendenkrans (Silver Laurel) of the Concertgebouw and after his retirement, initiated a concert series in the Lutheran Church in Amsterdam - later known as the Sonesta Domed Hall – where at least one Dutch composition was included at each concert.

During an event organized by the Buma, Van Delden openly criticized the government for the lack of making music within in the regular school system. One thing that really bothered him was that the Dutch showed little interest in music education and their own musical culture. In his opinion “conservatories and music schools should inspire their students to become more interested in contemporary music.” An admirable composer, a man with great social dedication and of utmost musical enthusiasm, died on July 1, 1988. His name was Lex van Delden.

Sources

Archives Van Delden (Netherlands Music Institute, The Hague)

www.lexvandelden.nl

Hiu, Pay-Uun & van der Klis, Jolande (red.) Het Honderd Componisten boek: Nederlandse muziek van Albicastro tot Zweers (Haarlem, 1997)