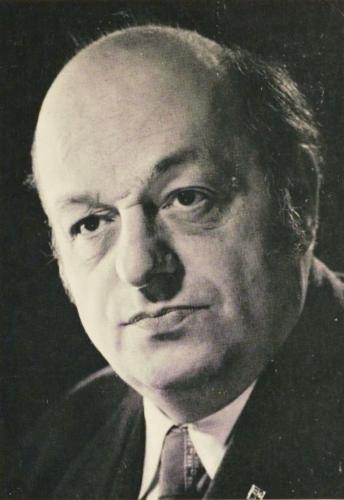

Hans Krieg

The life of Hans Krieg, a German who became a Dutch citizen in 1951, was marked by the horrors of Nazi ideology. Before the war, a promising career as a composer and choral and opera conductor was on the horizon, however, when Hitler and the Nazi Party came to power, Krieg, as a persona non grata had to flee his homeland. He managed to establish a new life in the Netherlands, but after the war he had to rebuild his life. Once more he succeeded, and this humble man was recognized as a key figure in the Jewish community.

by Aagje Pabbruwe

Advocate of Jewish heritage

Hans Max Krieg was raised in the family of a Jewish manufacturer of leather goods. Music played an important role in the family home. At the age of six he played the piano and began composing two years later. With his remarkable talent, it was obvious that he would choose a career in music. For composition and conducting he had the best teachers of his time, like Humperdinck in Leipzig, and Ochs and Von Rezniček in Berlin.

As of 1923, Krieg worked as a choral accompanist, opera conductor and composer of theatre music at the leading theatres in Germany and Zürich. In 1928, he expanded his career in Breslau. Despite the increasing anti-Semitism he was able to develop his capacities to the fullest. He conducted the largest labor union choir of Silesia as well as the choir of the Jewish Congregation. His love for the voice is apparent in a series of vocal works, showing a refined, poetic quality, in late-romantic style, revealing the influence of the composers he admired: Brahms and Mahler. His music set to Franz Werfel’s Paulus unter den Juden was enthusiastically reviewed, mentioning the “schöne Partitur.” Max Brod, another renowned author, also showed interest in Krieg's compositions. Krieg would always write tonal music.

Hans Krieg was the only member of his family who practiced the Jewish faith. As a young man, he was engaged a few times to non-Jewish women, but eventually married the Jewish-Romanian Regine Sternlieb in 1929. In 1930, their daughter Susanne was born.

A new life

In April 1933, caricatures of Krieg appeared in Nazi magazines, leading to his immediate escape to the Netherlands with his family, brother, sister, mother and mother-in-law. That same year his daughter Miriam was born in Amsterdam. It certainly wasn't easy to build a new life in a foreign country. There was hardly any opportunity, certainly not as an opera conductor, regardless of the great career he had already achieved. Krieg knew he had to change course and took on everything to support his family.

He copied numerous scores, wrote articles about Jewish music and musicians for encyclopedias, composed music for radio plays, taught music - also jazz – was broadcaster, conductor, organist and choirmaster, accompanist and elocutionist, among other things. In those years he wrote for the political cabaret show of the VARA radio, chansons and songs with a socialist character for Ernst Busch, Dora Gerson and Chaja Goldstein. He was also deputy choirmaster at the Liberal Jewish Synagogue and conductor of the Joodsche Orkestvereeniging Amsterdam (Jewish Orchestral Society Amsterdam). In no time he assimilated into Dutch society, as is evident from his 1938 celebration song on the occasion of Princess Beatrix's birth, performed by Jo Vincent.

During the war he collaborated on lectures about Jewish songs, organized by the Jewish Council's department of culture. It was a gloomy time; work was scarce due to anti-Jewish regulations and life was dominated by constant fear of being arrested. In May 1943, the family was ordered to move to the Afrikanerplein, an exclusively Jewish quarter. One month later Krieg was arrested during a raid and shortly after that, the family was deported to Westerbork.

Music is food for the soul

Krieg managed to carry on with music making and composing in Westerbork. For the “Tuesday revue” he was arranger, rehearsal pianist and accompanist, and played in the orchestra. This gave him certain privileges, like exemption from service and permission to use one of the grand pianos in the main hall. He also directed the children's choir and taught music and singing to fellow inmates. He sang to keep morale high, accompanying himself on the guitar he had brought from Germany. The family escaped transport to Auschwitz twice, due to hospitalization of the children and the third time thanks to Krieg's mother-in-law. She managed to get the family on the “Palästina-Austausch” list of the Red Cross, which meant the “privilege” to be transported to an exchange camp. In January 1944, the Krieg family was transported in a stock car to the “Sternlager” in concentration camp Bergen-Belsen where they remained until their liberation. Palestine was far away. Krieg was put to work in the shoe factory, his wife in the soup kitchen. Krieg's motto was “Music is food for the soul.” Despite all the hardships, and against orders, he managed, with his tenacious determination, to cheer up fellow prisoners and children by singing Dutch and Hebrew folk songs together.

When liberation was imminent, the Kriegs were evacuated to Theresiënstadt with the last train known as the “lost transport.” For days the train maneuvered aimlessly between the front lines. The passengers of this ghost train were finally freed near Tröbitz on April 23, 1945 by the Red Army. The Kriegs returned to the Netherlands in June, one of the few surviving families of Bergen-Belsen. Because they were not Dutch, they were detained in an internment camp in Limburg, along with members of the NSB, the Dutch National Socialist Movement. After this frightening episode, Krieg, severely weakened, was hospitalized until late July. His brother and sister, both in mixed marriages, survived the war. Krieg's mother and mother-in-law were murdered.

Once again a new beginning

Despite all the misery and personal losses, Krieg was determined to make something of his life. In October 1945, he advertised in the Nieuw Israëlietisch Weekblad, as teacher, ecolutionist, conductor, accompanist and musicologist, calling himself “a composer of Hebrew and Yiddish songs and music.” In November, he started performing again. Just as before the war, he managed to work in many disciplines: as accompanist at concerts in the synagogue, conductor of the Dutch Operette Amateur Society, opera choir “Euterpe,” singer, broadcaster, musicologist specializing in Jewish music, copyist of scores, composer and teacher. During the post-war reconstruction many benefited from his pedagogical skills. In Apeldoorn he gave music lessons, even in Hebrew, to around five hundred children; taught Jewish liturgical and secular music at the Amsterdam Music Lyceum, conducted Jewish children's choirs, wrote many witty children's songs and toured the country to lecture on Jewish music. He wrote more than thirty academic publications on Jewish music.

His grandfather was a chazzan (cantor); perhaps this explains Krieg's passion and ultimate goal to collect Jewish folk and liturgical music, Hebrew and Yiddish melodies and songs, and to republish and spread it throughout the community. He studied ancient music sources, listened to chassidic singers, and then made piano or orchestral arrangements.

Ernest-Bloch Award

Krieg depicted himself as a torn man, neither at home in Germany nor in Israel. But if ever he felt safe, it was in Amsterdam, behind the desk in his study, with his piano and extensive library. Here - apart from his early theatre music, cabaret songs and music for radio plays - he created an extensive oeuvre of works in all kinds of shape and genre, ranging from (children’s)songs to vocal compositions for solo voice, duets and choir with piano or orchestral accompaniment in German French Dutch, Hebrew and Yiddish, to works for piano, chamber music and melodrama. He had his own publishing house, the “Jewish Music Editions Kadimah,” based at his home address in the Waalstraat. All his scores, hand-written with much accuracy, look like printed matter, and were multiplied by a photo reproduction company. His post-war compositions in particular have a

Jewish character. For example Eli-Eli, honorably mentioned in 1947 by the jury of the American “Ernest Bloch Award,” and awarded with a shared prize for best Jewish composition of that year. It was performed in Tel-Aviv and broadcasted on radio. This recognition strengthened Krieg's confidence. That same year he wrote Waar bleven de Joden van ons Amsterdam? (Where are the Jews of our Amsterdam?), an imposing song in memory of the tens of thousands who were deported from the Hollandse Schouwburg in Amsterdam. A few years ago his daughter, singer Miriam Krieg, discoverd this score and made a recording. While researching in the library “Ets Haïm” of the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, Krieg discovered the cantate Le-El Elim by Abraham de Cassares from 1739, and provided it with an arrangement. This work received wide press coverage. In 1954, Krieg won international acclaim with the Ernest Bloch Award for Ani chavatselet (I am a lily) for three-part women's choir, soprano and tenor solo with piano or orchestral accompaniment, set to a text from the Song of Songs. As far as we know his opera Jeremias, on a libretto by Stefan Zweig, was never completed. Noteworthy is his transposition of the archaic music signs of the Lamentations of Jeremiah into modern Western notation. In 1959, the music libraries of the “Hebrew Union College” of New York and Cincinnati – the largest Jewish music libraries in the world – were interested in microfilming his entire “Jewish oeuvre.” Unfortunately this never happened.

Choirs

Choral music was of particular interest to Krieg. In 1946, he revived with passionate determination the “Amsterdams Jewish Men's Choir.” Four years later he established the women's choir “Hasjier Hajehoedie.” For both choirs he composed a cappella works and arranged Jewish songs and hymns. Through great perseverance these choirs enjoyed a reputation in the Dutch music world and abroad; they were frequently broadcasted on radio and television. The men’s choir toured Israel and was invited to participate in Israel's “Zimriya” choral competition. This was also a research trip for Krieg. Both choirs sang at the inauguration of the Antwerp and Rotterdam synagogues. In May 1955, Krieg and the men's choir sang at Bergen-Belsen and shortly after he established a vocal quartet aimed at performing on memorial and celebration days. A highlight was the performance in 1960 of his requiem Jiskor, a six movement memorial symphony for eight-part mixed choir, soloists and orchestra, dedicated to the Jewish victims of World War II. Radio Jerusalem broadcasted this work on the national day of remembrance in Israel. After Krieg's death the two choirs merged and performed from that time on as “Verenigde Joodse Koren Hans Krieg” (United Jewish Choirs Hans Krieg), in honor of their passionate founder and conductor.

Krieg’s melodic voice made him the ideal performer of the Jewisch repertoire. For many years he gave concerts and lectures throughout the country, and on radio and television, for Jewish as well as all other audiences. He and his daughter Mirjam were a close-knit team. He accompanied her and they presented evenings on the history of Jewish music. They did a great deal to preserve Jewish musical heritage. Their glowing performances attracted packed houses. They released two LP recordings on the Philips label; a third album in the planning, never materialized due to Krieg's unexpected death. On November 26, 1961, during a choral rehearsal, Krieg felt unwell, and he died on that same day of heart failure. A memorial concert took place in the Amsterdam Bach Hall on March 10, 1962. His ex-libris, designed by Alice Horodisch-Garman, depicts a lyre whose strings ascend from a heart and a bird in upward flight – very appropriate for the versatile Krieg, who devoted, with heart and soul, his entire life to music.

Sources

Archives Hans Krieg – Netherlands Music Institute, The Hague

Archives Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie, Amsterdam

Newspaper archives Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague

Thanks to Mrs. M.H. Krieg