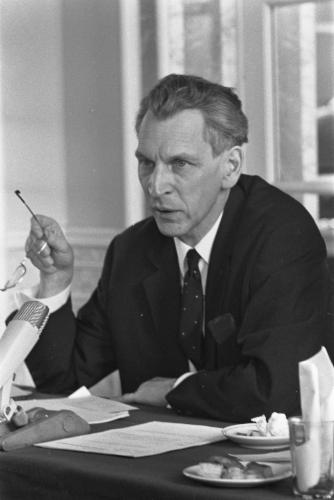

Marius Flothuis

Marius Flothuis led an eventful life. Early on, he was politically aware and left-wing orientated. He lost his job at the Concertgebouw Orchestra on his refusal to register with the Kultuurkamer, a regulatory cultural agency installed by the German occupying forces during World War II. He was arrested for his resistance work, imprisoned in Camp Vught and deported to Sachsenhausen in 1944. Meanwhile, he continued composing and survived the hardships. In the postwar Dutch and international music worlds he held numerous positions.

by Joyce Kiliaan

Composer, scholar, humanist

Marius Flothuis, born on October 30, 1914, in an Amsterdam apartment on the corner of Ruysdaelstraat and Hondecoeterstraat, was raised in a well-to-do family. His father played the violin and as a child, he loved listening to his mother playing Mendelssohn's Lieder ohne Worte on the piano. Around 1920, he learned the basics of piano playing from his brother Joop, who was five years older. It was not long before he surprised everyone by playing Pleyel's Piano sonatine in D major. From then on, music never truly let go of him. His piano teachers were his uncle George Hamel, Bé Boef, Arend Koole and Hans Brandts Buys. Especially Brandts Buys, his music teacher at highschool was of prime importance; a stimulating mentor to Marius.

Highly gifted and versatile

Marius Flothuis was a timid, withdrawn boy, but his talents were gradually recognized at the Amsterdam Vossius Gymnasium. At fourteen, he surprised his piano teacher Koole with his own cadenzas of Haydn's Piano Concerto in D major, and soon after, his cadenzas for Mozart's piano concertos. At this time, he often played piano with his brother Joop, mostly symphonic repertoire arranged for four hands. Joop introduced him to the music by Debussy, Ravel and other French composers; it an enormous revelation.

Marius was fifteen when he performed on the piano at the high school's musical evenings for the first time. Hans Brandts Buys wanted him to play piano, arrange music and stimulated him to conduct the school orchestra. Marius became strongly influenced by contemporary composers. He felt challenged by Hindemith and Milhaud to composed string quartets, but these soon were burnt in the stove. At seventeen, he passed his high school exams and also the piano and theory exams of the Royal Dutch Music Association (kntv); his program included Mozart - with his own cadenzas - and a composition by Willem Pijper.

Marius – since his school days known as “Flot” – was just seventeen when he attended the University of Amsterdam to study classical languages. A year later he drew attention from the press as the composer of music to Sophocles' tragedy Philoctetes. Simultaneously, he studied musicology in Utrecht and later in Amsterdam. As a subscriber of two orchestral series, he was a “regular” at the Amsterdam Concertgebouw. At eighteen, he wrote to the board of the Concertgebouw Orchestra, eight pages of valid arguments criticizing their programs. Despite this, he was appointed in 1937 as assistant artistic director. It was the beginning of a long-term engagement - with a break from 1942 to 1953 – that continued until 1974. Between 1946 and 1950 Flothuis was employed as a librarian at the Donemus Foundation, and from 1945 to 1953, as a music critic for the newspaper Het Vrije Volk.

Flothuis was appointed professor of musicology at the University of Utrecht in 1974. He also lectured at several European universities and in the United States, until his retirement in 1982. His academic aspirations and managerial experience proved useful when he was chairman of the Zentralinstitut für Mozartforschung (Central Institute for Mozart Research) in Salzburg, a position he held from 1980 to 1994. During that time Flothuis also maintained his pivotal role in the Dutch music world. He served on numerous boards, was active in musicology, engaged in performance practice, sustaining his contacts and friendships with international musicians, conductors and composers. He was a leading figure in many areas. Through the years he continued composing as well as publishing numerous academic articles.

Sincere, sensitive and vulnerable

Marius grew up in an affluent family, with many opportunities, but the relationship with his parents lacked warmth. In the 1930's, he was a member of the Independent Socialist Party (OSP), while his father became a “secret” member of the Dutch fascist party (nsb) upon its establishment in 1931. From that moment on, fierce debates took place between father and son. In 1934, Marius fell in love with Lenie Sternheim - she was half-Jewish - they married in July 1937; their first daughter was born in December of that year.

Marius took on anything to make ends meet and he quit his studies. The Concertgebouw Orchestra gave him a small job. In May 1939, his Vier liederen voor sopraan en orkest (Four songs for soprano and orchestra) premiered with the orchestra under the direction of Eduard van Beinum. This marked his debut as a composer. He composed a lot during this time, but misfortune was around the corner. His wife was romantically involved with composer Bertus van Lier. After a few years, this led to the legal separation which the couple had postponed for far too long. When Flothuis, active in the resistance, was betrayed and arrested on September 18, 1943, their marriage was already desolved. But just before his arrest, he had already been fired from the Concertgebouw Orchestra because he had refused to become a member of the Kultuurkamer.

When he finally returned from Sachsenhausen in 1945, he didn't get his job back at the Concertgebouw Orchestra. After a period of rehabilitation in a sanatorium in Doorn, he started working as a librarian at Donemus in 1946. Four years later he was again unemployed. In the meantime, in 1948, Marius had fallen in love with Roosje Voorzanger, a Jewish survivor of Auschwitz-Birkenau; they married in 1953.

In that same year, Flothuis was again appointed as assistant artistic director of the Concertgebouw Orchestra and two years later, artistic director, a post he held until 1974. Then, in his own words, the happiest period of his life began when he worked as a musicology professor at the University of Utrecht. But once more misfortune struck when his second wife died, unexpectedly, in 1978. After his retirement in 1982, Flothuis continued publishing papers. In the early 1980s he found his third partner in the musicologist Silke Leopold, 34 years his junior. Marius Flothuis died in Amsterdam on November 13, 2001.

War experiences

His history teacher at the Vossius Gymnasium, Jacques Presser, was of great influence on Flot's early political awareness. He looked up to his older brother and they both became members of the left-wing osp. Deeply shocked and extremely anxious, Flothuis experienced Hitler's seizure of power on January 30, 1933. His fear would only increase by media reports and after reading Wolfgang Langhoff’s Die Moorsoldaten, a pragmatic story about a soldier's hard labour in harsh conditions, which Flothuis would later experience himself.

The fascists were also effecting the music world. In 1934, he noticed that a piano reduction of the Dreigroschenoper by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill was no longer available, and a reprint was not planned. He witnessed the large groups of German refugees now arriving daily in the Netherlands. A month before the Kristallnacht of November 9, 1938, he wrote the poem Mijn kind (My child) expressing his concerns about the society in which his daughter was growing up. At the Concertgebouw Orchestra, he witnessed how composer Egon Wellesz, after the premiere of his work, immediately left for England, fearing the danger to return to his homeland, Austria. Because Flothuis was increasingly confronted with the “new order,” which meant all kinds of implementations imposed on Jews, he rebelled. Jewish refugees were permanently hiding in his home. Besides illegally possessing a radio, he distributed clandestine magazines, and even organized forbidden house concerts to raise money. On Saturday, September 18th, 1943, things went very wrong. Three policemen raided his house on the Stadhouderskade and Flothuis and his “guests” were arrested. After some time in the prison on the Amstelveenseweg in Amsterdam, he was deported on November 28th to Camp Vught.

Despite degrading conditions in the camp, he was, amazingly enough, able to compose and make music. The captives were informed about D-Day (June 6, 1944) and on Mad Tuesday (September 5, 1944) there was a glimmer of hope as rumors spread that the Liberation was imminent. However, during the role call, several hundred of Flothuis' fellow prisoners were randomly selected and executed immediately. The next day he was transported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp and lost all contact with the outside world. The last weeks of the war were indescribable. The SS was cornered and put thousands of weary prisoners on a death march. From April 21st to May 4th, Flothuis walked from Sachsenhausen near Berlin to Schwerin on the Baltic Sea. Many died along the way. He survived, although severely weakened from all the hardships.

After some detours, Flothuis returned to Amsterdam on May 29th and upon his return had to deal with his mother's suicide, just eight days before, without knowing that her son had survived. One week later, he and violinist Nap de Klijn premiered his Variatie op een Oud-Nederlandsch lied (Variations on an Old Dutch song) in the Main Hall of the Concertgebouw.

The ideals Flothuis had fostered in his youth remained throughout his lifetime unchanged. First an introvert child, raised in a protective environment, encouraged by classmates and teachers at the Vossiusgymnasium, and developing into an enthousiastic and succesful student. During the horrors of 1940-1945, he and his fellow prisoners were not only confronted with Jewish victims, but also with criminals, murderers and torturers. The spirited, gifted youngster became a discerning and wise man with a huge circle of friends and acquaintances, always looking for a harmonious solution when disagreements arose.

His music: everything but opera

As a composer, Flothuis, was initially fascinated by the Viennese School; however he was also influenced by Hindemith, Milhaud and Pijper. But he soon developed his own style, characterized by the balance between form and content on the one hand, and form and instrumentation on the other. And this was done with clarity and great precision. Although by some called a neoclassicist composer, he wasn't afraid to experiment with any compositional style, even dodecaphony. Virtuosity is another thing he didn't eschew, as seen in the piano work Paesaggi, dedicated in 1990 to pianist Sumiko Nagaoka. Another characteristic of his music is the absence of any expression of power or violence, or massiveness of overwhelming tutti sections.

In the war years, Flothuis composed mainly for friends; in his “camp period,” for his fellow prisoners, in total some twenty-five works. In 1944, imprisoned in Camp Vught, he composed Valses sentimentales for piano four hands, dedicating it to his wife. This piece is reminiscent of Schubert's lyricism. Poignant in his vocal compositions, are the expressive texts, often related to nature or left-wing ideals; the words always determining the direction of his music. In his own words, he composed open minded in the 1950s; in fact it was only years later that he focused on more open and free forms like those of Debussy. Flothuis indeed felt akin to the French spirit. He said later: “I'm actually an incredible traditionalist.”

In his music he does not seem to be influenced by his war experience. On the contrary, it strengthened his compositional ideas. In addition, he opted for the absolute in art. He despised composers, who with their music reflected “suffering, war or heinous crimes.” Flothuis was averse to showing off his own sorrow and that of millions of others. This exemplifies his humble nature as an artist, scholar and humanist. He was utterly sophisticated. In spite all this, the war had scarred his life forever.

Sources

Kiliaan, Joyce, Marius Flothuis (Amsterdam, 1999)

Overbeeke, Emanuel, ‘Marius Hendrikus Flothuis’, in: Jaarboek van de Maatschappij der Nederlandse Letterkunde te Leiden 2002-2003 (Leiden, 2004)