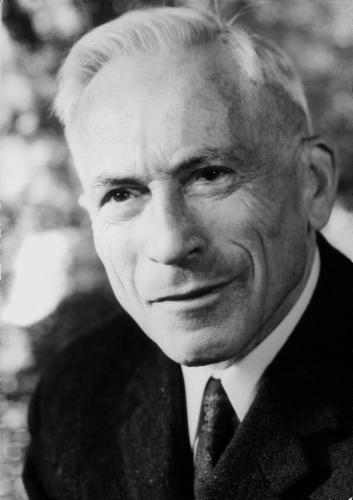

Wilhelm Rettich

Wilhelm Rettich belonged to that generation of those whose work and life was deeply affected by the First and Second World Wars. Captivity, persecution, hiding and losses scarred his life. In 1933, he emigrated to the Netherlands, where he survived the war in hiding. Rettich worked a great deal for the radio, a young and progressive medium at that time. Although he became a Dutch citizen after the World War II, he returned to Germany in 1964.

by Diet Scholten

A Survival Artist

He was born in Leipzig in 1892, the son of Isidor Rettich, a merchant and Rosa Idelsohn. His parents wanted him to become a doctor, but he knew early on that music was his destiny. His mother came from a musical family and gave him his first piano lessons. At seventeen he studied composition with Max Reger at the Leipzig Conservatory. He worked as an assistant répétiteur at the Leipzig Opera and as a conductor at the Stadttheater in Wilhelmshafen.

Wanderings

Rettich's musical career was interrupted with the outbreak of World War I. He was enlisted in the army as first clarinetist in the infantry's band, but was soon conscripted to fight on the Russian front. In September 1914, he ended up as a prisoner in various Siberian camps. There he organized an orchestra and they made their own instruments. During his captivity he composed the one-act opera König Tod on scraps of paper, based on a fairytale written by fellow prisoner Franz Lestan. The work premiered in 1928 in Stettin, with Rettich conducting the orchestra.

After the Russian revolution in October 1917, he spent several years in Tschita, a city in south east Siberia. To make a living he taught piano, particularly to refugees from St. Petersburg and Moscow. Meanwhile, he spoke the Russian language fluently and he composed songs set to Russian poems, by Lermontov, among others. In an interview in 1972, he recalled this relatively happy period, despite the many epidemics.

He finally returned to Leipzig in 1920, after having worked in Shanghai, Trieste and Vienna. Back in Germany he became Kapellmeister in Köningsberg and Stettin, working as a conductor for the radio orchestra, and composing music for radio plays at the Mitteldeutsche Rundfunk Leipzig. Radio at that time was still a young and progressive medium and there were live broadcasts of many concerts. Rettich also led the choir of the liberal Jewish congregation in Leipzig's Great Synagogue.

Berlin and emigration

In 1929, Rettich married Bertha Müller; the couple divorced in 1935. He moved to Berlin in 1931 and became conductor at the renowned Schiller Theater, and with the Berliner Rundfunk Orchestra. Berlin was the “place-to-be” and in Rettich's own words, “You either were there, or you went there.” An important composition of this period is Fluch des Krieges for soloists, choir and orchestra, on a text by the Chinese poet Li-Tai-Pe (1932). This work shows his radical pacifistic views in reaction to the catastrophes of World War I. “Cursed be the war, cursed the work of weapons, a wise man has no part in their madness.” He also composed a song cycle in the period 1923-1928 of twenty-six songs set to texts by Else Lasker-Schüler, a bohemian Berlin poet.

The seizure of power by the Nazis in February 1933 put an end to Berlin's flourishing cultural life. Rettich's friend, conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, had already forewarned him. And rightly so: Rettich immediately got a berufsverbot (an order to cease his professional activities); as a Jew and pacifist, he was a persona non grata. The doorman at the broadcasting building had orders to stop Rettich from entering; he was fired but received his salary and fled immediately. Via Prague, he arrived in May 1933 in Amsterdam, destitute and without work. Yet several friends in exile were awaiting him. The following month he gave a concert with singer Paula Tarko and cellist Robert Felix Mendelssohn. The hall at the Muzieklyceum was too small; there was great interest in this concert by three Jewish refugees from Berlin. Actually Rettich was planning to travel further, but he enjoyed his new life in the Netherlands. He was not the man to succumb to pessimism, and established himself as a music teacher in Amsterdam. First he changed his name to the Dutch equivalent, Willem. As of 1934, he lived in Haarlem and earned a reputation with the concert performance of Weber's opera Der Freischütz. The success of the opera's broadcast by the vara radio was so enormous that another performance followed in The Hague, graced by the presence of Queen Wilhelmina.

He set music to Dutch poems by Boutens, Gezelle and Gresshof. Commissioned by the vara radio, he composed the Eerste Mei Cantate (Cantata for Labour Day – May 1st). At the music school in Haarlem he taught piano, music theory and was also head of the orchestra class. In 1938, he was the founder and first conductor of the Haarlem Symphony Orchestra, an amateur orchestra that still exists today.

Composing while in hiding

The German occupation in May 1940 prohibited Rettich from working. In 1941, the radio underwent a hostile takeover by members of the Dutch Nationalist Party (nsb), which ended his fixed source of income. He still organized house concerts and taught, but as of 1942, he went into hiding in Blaricum at the home of a former piano student. Now he lived right across the street from musicologist Caspar Höweler, whose music library he consulted, in secret, and as frequently as possible. His mother and younger brother were in hiding in Haarlem, but they were betrayed and in 1943 murdered after deportation by the Nazis.

Rettich's period in hiding was very productive; he composed until late into the evening by candlelight. He also read Dutch literature to get inspiration for future librettos. However he never played the piano; his former pupil was just a beginner, and Rettich feared that passers-by might become suspicious if they suddenly heard complicated chords. Nevertheless, he managed to write a number of compositions incorporating Jewish themes. For example the Symphonischen Variationen für Klavier und Orchester with a theme from the Hebraischen Liederschatz by Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, a distant relative. He dedicated this work to his murdered mother. On June 8, 1950, the Haarlem Orchestral Society premiered this extremely pianistic and virtuoso work with George van Renesse as soloist. The Sinfonia Giudaica also dates from this time; a key work that was performed for the first time thirty-five years later in Frankfurt. In its slow movement, he cited the Kol Nidrei, and in the finale, hope breaks through on the melody of Hatikvah, Israel's National Anthem. He dedicated this work to the victims of the war.

Rettich's music can be considered late Romantic, influenced by Strauss, Schreker and Korngold. He certainly was not an innovator. His aim was to write comprehensible music, to convey his humanistic and pacifistic message. The critic Muller called him in the daily De Telegraaf (December 9, 1958) a genuine romantic “unwilling to hide his feelings by adorning them with fake fashionable notes.”

After the war

After the liberation, Rettich returned to Haarlem. He had an extreme aversion to anything German and became a Dutch citizen by naturalization. He worked in The Hague, and in Amsterdam as conductor of the Hoofdstad Operette, founded in 1945, but that job wasn't very challenging. In 1946, he had met the singer Elsa Barther and they were married. She would perform many of his songs in subsequent years. Rettich's music was regularly broadcasted on Dutch radio in the 1950s and 1960s.

Artistically, working in the Netherlands was, in the long run, not satisfying enough. In 1964, the couple Rettich returned to Germany and settled in Baden-Baden. In a newspaper interview on the occasion of his 75th birthday, he said: “Germany is the land of music drama and opera. And it has a music scene, more vibrant than anywhere else.” Rettich worked for another twenty years as a composer and conductor in Baden-Baden. He received recognition, was awarded with the Bundesverdienstkreuz (a Federal Cross of Merit), and even became an honorary citizen of the city. On the occasion of his 75th and 80th birthdays, concerts of his music took place in the Netherlands, and articles and interviews appeared in the various media. He was certainly not forgotten in the Netherlands. Rettich died in Baden-Baden on December 27, 1988. Twenty years later, a memorial tree was planted there in memory of this extraordinary musician and human being.

Sources

Rainer Licht: Wilhelm Rettich, in: Lexikon verfolgter Musiker und Musikerinnen der NS-Zeit, Claudia Maurer Zenck, Peter Petersen (Hg.), Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, 2006

Siebe Riedstra, review CD Else Lasker-Schüler Zyklus, www.opusklassiek.nl (2012)

Boss, Gideon, CD-booklet Wilhelm Rettich, Else Lasker-Schüler Zyklus Op. 26A (Gideon Boss Musikproduktion, 2006)

Newspaper archives Koninklijke Bibliotheek, The Hague

Wilhelm Rettich estate